Today’s song is from the harmonious Civil Wars – Oh Henry. Artwork above © Lauren Delora Sears.

As I get older, I appreciate the white space more and more. Designers know that the white space is as important as the rest. It provides context, balance and a container in which to arrange the content so we can easily find and navigate through the important stuff. The white space in our lives gives us room to step back and reflect. And it is this process of reflection that consolidates our learning and sparks creativity.

The hustle and bustle of life in the modern world barely offers a nanosecond of time for reflection. We rush from one thing to the next, be it job, project, relationship or adventure – always focussed on efficiency, productivity, utility and economy. It is hard to imagine a world where you had the means to pursue a career entirely of your own choosing, and construction, with little regard for the mundane necessities of ‘real world’ existence that plagues us all. The freedom to follow your heart or intellectual curiosity is a precious gift which is rarely afforded to us.

For academic researchers, the importance of this freedom and time for reflection is embodied in sabbatical leave. The notion that it was a frivolous exercise and a complete waste of time has been raised several times throughout history. But it is often when reaffirmation and rejuvenation take place. The loss of such a crucial part of the research process would be lamentable. Increasingly, research is expected to become more applied. With limited funding available for science research there is an expectation of a payoff. And sooner rather than later. So something has to give with the burden of administration, teaching and research all competing for time. Dr Tamson Pietsch notes that many researchers now do research in their leisure time.

The demands placed on the scientific research process by the modern obsession with utility and economic evaluation could have a profound effect on our ability to adapt to a rapidly changing environment. This myopic vision reduces research diversity and alters the process and direction of intellectual endeavour.

I see this appropriation of scientific potential and subsequent loss of diversity as akin to a population bottleneck. There are many instances where the value of particular research has not been realised until much later. It takes time to acquire knowledge, build upon it, reflect upon it and stimulate creativity. As Dr Pietsch points out, fishing for ideas is like fishing for trout – it takes time. You can’t force creativity no matter who is doing the table thumping. So in the event of a concentration of research in favoured areas the ability to switch focus, and resources, will be compromised.

Fortunately for us, there have been individuals throughout history, who have had the time for research and reflection without some of these constraints. Their contribution to science today is immense largely because they were not hamstrung by bureaucratic, political or financial impositions. They were known as gentlemen (they were usually men) of independent means. Included among them was the famous Charles Darwin (evolution).

But another, hardly known outside of geological circles was Henry Clifton Sorby.

In the year that Queen Victoria became monarch of the United Kingdom he was only 11 years old. By the time he had turned 15 he was already determined to pursue a life in science.

In a bittersweet turn of events, Henry’s father died, leaving Henry a sizeable sum. It was enough, in fact, for him to become one of those gentlemen of independent means at only 21 years old. It is hard to imagine your average 21 year old, these days, choosing to pursue a life of science, in their leisure time, when such a windfall comes their way! But that is precisely what he did.

Marine science, geology and metallurgy fascinated Henry. He sailed around the North Sea coast indulging his interests in marine biology and geology. He’d collect small marine organisms which he then meticulously prepared and mounted on glass slides. Henry soon realised that the microscope could also be used to view rock samples in a very different way.

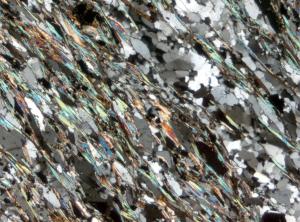

First, he pioneered the techniques for examining rock in thin section. It is now the standard method by which geologists come to understand the origins of rocks. For Henry, it would have been a laborious task, hand grinding the rock down to slices “1000th of an inch” thick. This allowed light to be transmitted through the previously opaque rock, revealing detailed structure and micro-textures.

Thin section showing aligned minerals in the structure of the rock © GNS Science.

Poor old Henry was initially laughed at for attempting to view ‘mountains’ under a microscope. However he persevered and thank goodness he did! He went on to find microscopic fluid inclusions within the mineral grains. These tiny bubbles of liquid or gas are trapped within the mineral, at the time of its formation. They provide clues to the temperature and pressure conditions which existed at that time. His pioneering work with the microscope laid the foundation for modern petrography – analysis of those detailed structures and textures.

A modern petrographic microscope, used to look at thin sections, is different from the standard microscope that biologists use. The petrographic microscope has the addition of two polarising filters, oriented at right angles to each other, and a rotating stage which the sample sits on.

Cross polarized light © Olympus Microscopy

Light, travelling up from the its source at bottom of the microscope, passes through the first polarising filter before reaching the sample. Only light vibrating in a direction aligned with the polariser is allowed through. This is called plane polarised light.

Thin section under plane polarized light © GNS Science

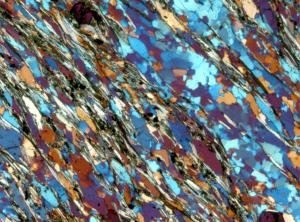

A second polarising filter is located above the sample and this can be turned on or off. When it is turned on the plane polarised light is blocked (crossed polarised light).

Thin section under cross polarised light © GNS Science

Olympus Microscopy have a good interactive tutorial that allows you to play around with changing the angles of the polarising filters.

Rotating the stage makes some minerals appear black briefly when the polarisation prevents the light from getting through. Some minerals produce beautiful, vivid colours caused by interference during refraction of the light rays through the mineral. By careful examination of each mineral’s different optical properties geologists can begin to reveal the composition and origin of the rocks.

Vivid colours produced by interference © GNS Science

Present day geologists owe a great deal to the efforts of Henry Clifton Sorby and others who were lucky enough to have time to think and pursue their interests at their leisure. And we all can appreciate the artistry and histories revealed by Henry’s unwavering commitment and passion for his science.