Song for this week is Tool’s Flood.

This week, for the second time in two weeks, I had to make the trip between Christchurch and Dunedin during a severe weather warning.

At the start of Easter, my classmate and I left Dunedin and headed for Christchurch. It was the start of a ten day break and we were both looking forward to going home to be with our partners. I was staying in Christchurch but she was flying out in the very early hours next morning bound for Sydney.

I picked her up just after lunch and we began the five hour journey by car. There was a severe storm approaching, and we had been warned to take it easy, but I have driven that road many times before and it didn’t really faze me. Rain had been plummeting from the sky for several days, on and off, and the ground was pretty well saturated. Tiny creeks, at the side of the road that were usually barely noticeable, frothed in a cappuccino cascade. The waves crashing in on the stretch of beach at Katiki were wind-whipped and wild so we stopped, very briefly, to try to take some pictures. Not a chance! Gusting gales and horizontal sprays of rain and sand on my lens, forced a hasty exit. The rain had plenty of time since it wasn’t due to get dark until 7pm. We’d be well home by then since I was happy to drive slowly and carefully and have several stops. Or so I thought.

Approaching Hampden, a small settlement between Palmerston and Oamaru, we noticed a line of traffic ahead of us. It looked like an accident or something further along the road so we waited patiently in the queue. We watched the traffic continue to come towards us from the other direction for about fifteen minutes. That seemed odd. I switched off the engine and we waited while the traffic behind us backed up. Still, the opposing traffic seemed to flow freely. After another ten minutes, we saw a bedraggled man wandering down the full line of stationary traffic towards us. One by one, the windows of the cars in front of us rolled down and he leaned in for a few seconds to speak to the travellers inside. Then it was our turn.

“Bridge is closed at Maheno”, he said. Then he added, “Can’t go back to Dunedin either”.

The Kakanui River had flooded, yet again.

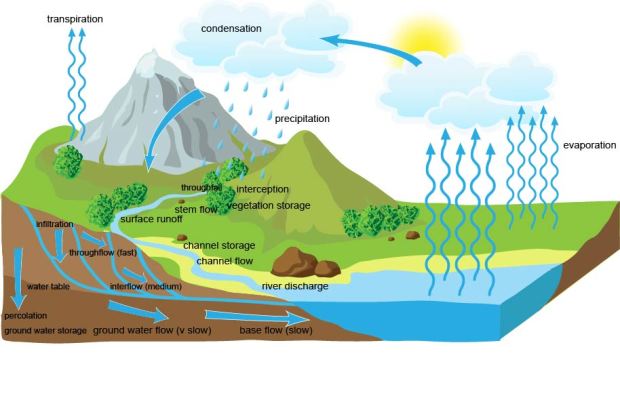

Records of flooding on the Kakanui go back to 1868 and, back then, damage extended over a wide area and people lost their lives. Its catchment area is almost 900 square kilometres. One quarter of that is in upland mountain areas with steep sided slopes and the river runs in a single thread or is slightly meandering. The steep ground means that more water runs straight off over the surface (runoff) rather than soaking in (infiltration).

Drainage Basin System credit: Andrew Bennett

Low rolling hills and valleys make up the remainder. They have gentle gradients and the river channel migrates and braids. On gentler slopes there is more infiltration than runoff – unless the ground is already saturated and can’t take any more. Rainfall is measured in mm and the highest recorded during a storm is peak rainfall. Flooding is the catchment’s natural response to a deluge of rain.

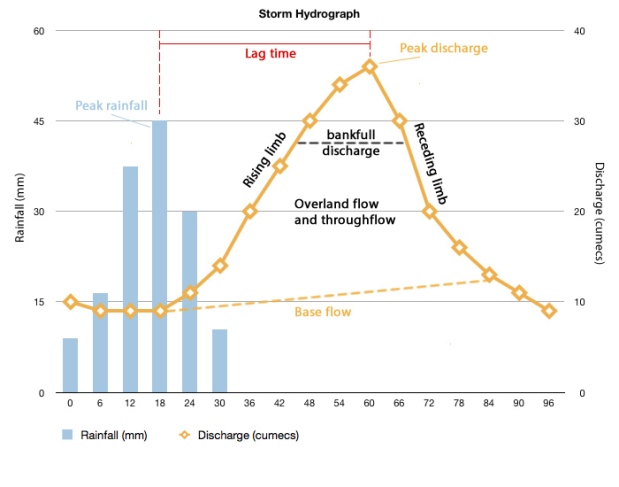

Hydrologists are interested in the characteristics of the river when it floods. The discharge is the amount of water flowing through the river at a given time and it is measured in cubic metres per second (cumecs). The highest discharge resulting from a storm event includes the water, sediment and other matter in the river. This is called peak discharge. Plotting this information on a hydrograph gives a sense of what is happening over time. The rising limb is the time that the river is experiencing increasing discharge. The receding limb shows the reducing discharge and return to normal flow.

Storm Hydrograph credit: Andrew Bennett

The time from the first rain drops to the time there is a change in the discharge is called the river’s response time. If rain keeps falling discharge keeps increasing and bankfull discharge is the maximum amount of discharge that a river can hold before bursting its banks.

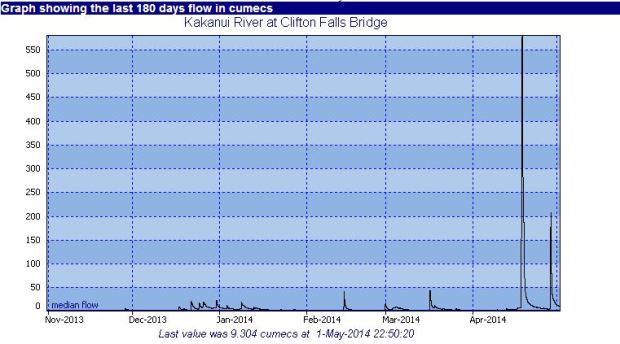

The problem we faced was that there was a lag time between the rain falling in the catchment and the time of peak discharge. The rain had been falling there for a while before we left Dunedin. It takes a while for the high flows to propagate downstream from the upper reaches. So flood alarms are tiggered when the rainfall at Clifton Falls in the Upper Kakanui reaches 40mm in 24 hours and there are several stages flood warnings depending on flow. Civil Defence is notified when it is flowing at 267 cumecs at Clifton Falls as this will be much greater downstream where State Highway 1 crosses it at Maheno. The road is closed once it reaches 420 cumecs here.

The Otago Regional Council graphs show the rainfall and flow at Clifton Falls Bridge and the summary of flow for that week showed a minimum flow of 6.3 cumecs and a maximum of almost 580 cumecs. No wonder we couldn’t get through! It would take a while for the river to recede.

Apparently, the traffic that had been driving past us had been either local residents or fed-up folk who had pulled out of the line. Every now and then the cars would creep forward to take up the vacant space.

Hampden, on Easter Friday, is not the best place to be trapped by rising floodwaters. The phone signal was intermittent but I managed to check traffic updates. It looked there would be an update within a couple of hours. Luckily, we were able to pull out of the queue once the car reached a small side road. We got out and went off to explore Hampden’s culinary delights and returned to watch a couple of sitcom episodes on our laptops.

Time was marching on so Elsie ventured out in the wet to check out the situation. We were told the road was closed until midnight. Waiting in the car for that amount of time was highly unappealing and it meant we’d get in to Christchurch just before 4am.

No question – we had to have a plan B.

“Are you up for an adventure?”, I asked.

“Sure”, was the reply.

I phoned my partner to find out the state of the Pigroot – the route from Palmerston through to Central Otago – an enormous detour but doable. He said there was some flooding but that it was still open. If the road opened at midnight we’d still have 8 hours of sitting around in the car and, personally, I’d rather be driving. It would take us at least 8 hours from here so we bolted for Palmerston.

We travelled inland through to Alexandra, past the Clyde Dam to Cromwell and up through the MacKenzie Country to Tekapo. Once we got near Alexandra, the rain eased and from there the rainfall was sporadic. By the time we got to Tekapo the skies cleared and we saw the new moon shining brightly. We made a small detour to stop at the Lake Tekapo for a few minutes to watch the moonlight reflect on the water and highlight the top of the hills behind the township.

Back on the road, it wasn’t long before the murk again filtered through Burke’s Pass. From here, the journey home was wet and miserable as we veered away from the shelter of the hills and ever closer to the East Coast.

Bleary-eyed, I pulled into the driveway just after 1am. We heard later that they had reopened the road at 8.30pm and we may have made it home a little earlier but I was pleased to have been doing something active rather than sitting and waiting.

While it is an inconvenience to be held up because of flooding it is important to take care. Thank goodness no-one has been lost recently although a woman was rescued from her car after being swept down the river as we were heading north!

I guess more flooding is something we’ll have to get used to, given the prediction of increased storminess, due to climate change. Understanding more about rivers and flood dynamics can help with travel planning at the very least. We’ll know for next time.