In Part 1, of Flames stand up for Hallelujah, I explained standing waves and used the immensely popular fire-breathing Ruben’s tubes to illustrate them.

We can now begin to explore particular lyrics of Hallelujah, the song by Leonard Cohen, that mentions “the fourth, the fifth, the minor fall and the major lift”.

To recap, standing wave patterns form from perfectly timed interference of two waves in a medium – passing along a string fixed at one end, for example. Take a quick look at the previous post if you need to refresh your memory.

So, while the waves travel in opposite directions they still have the same frequency. The frequency that produces a single standing wave on a given string is called its resonant frequency. That will change according to what it’s made from and its length, tension and thickness, among other things.

The lowest frequency that produces a standing wave is the fundamental. It’s also called the 1st harmonic. It looks like this:

The arrows show the oscillating movement of the string.

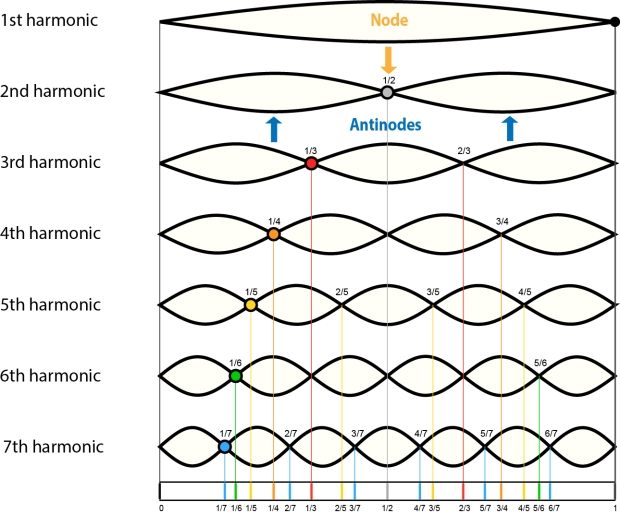

Any frequencies higher than the 1st harmonic are called overtones and they only occur at particular frequencies. The frequency that produces two standing waves, in the same length of string, is called the 2nd Harmonic (1st overtone). Three standing waves becomes the 3rd harmonic (2nd overtone) and so on. So each harmonic is a simple multiple of the fundamental.

Harmonics are the nodes of a vibrating string. After W axell

This is called a harmonic series. There are many different series because the fundamental can be any note. What is important is the relationship between the harmonics and that doesn’t change.

When it comes to musical notes, the distance between the 1st harmonic and the 2nd, is an octave. No matter which note frequency you start with the 2nd harmonic will always be twice its frequency. If one note, for example concert A, has a frequency of 440 Hertz (Hz) then A one octave above will be twice that at 880Hz and the one below will be 220Hz (half). In fact, any note vibrating at twice the frequency will be an octave higher so the 6th harmonic will be an octave higher than the 3rd. The eighth will be an octave higher than the fourth.

We can see that the ratio is 2:1 – the higher tone makes two vibrations in the time that the lower one makes one. Similarly, between the 2nd and 3rd the ratio is 3:2. That is, the higher tone makes three vibrations in the time it takes the lower one to make two. However, when a string is plucked the tone we hear is the sum of all its harmonics blended together. It’s what gives an instrument its particular sound.

The relationship between these frequencies is what determines whether notes played together sound good or not. If they sound good they are consonant; if they don’t they sound totally out of tune and dissonant. The lower the ratio, the more often the waves coincide and the sweeter the sound it has. The more dissonant frequencies have high ratios.

Chords are several notes played at once. Three notes played together form a triad which forms the basis of many popular songs. It is important to get the right combination of notes, though, or we end up cringing!

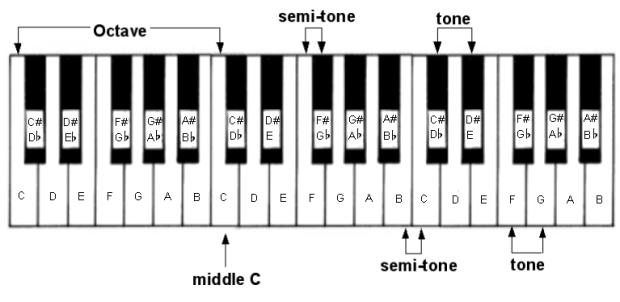

Pitches that are too close together sound “off” so a chromatic scale of twelve is used to make the steps all the same distance apart in an octave.

A musical scale is a set of notes ordered by fundamental frequency. Each scale is made up from a select bunch of 7 tones from the twelve no more than 2 and a half steps apart.

Two common scales are major (happy sounding) and minor (sad sounding). The key, is the starting note for the scale. Most people are familiar with the DO RE ME FA SO LA TI DO degrees of the scale – 7 tones plus the return tone to bring us home and not leave us hanging. Try singing it without the last DO and you’ll see what I mean! These 8 notes form the diatonic scale.

The C major scale has the notes C D E F G A B as shown on this keyboard:

Credit: Nicholas H Tollervey

Each chord is built from a combination of particular notes and there are 7 diatonic chords in the C major scale. Each has a function relative to the key note and they are designated with Roman numerals. Have a look at the “F”. It is the fourth note of the C major scale. The F chord built on this 4th note of the scale is called subdominant or IV. The G chord built on the 5th note is called dominant or V. So a chord progression from F to G is “the fourth, the fifth”. In this case the VI is the relative minor the so-called minor fall and the major lift is the progression from G to A minor (VI) back to F. Hallelujah!

It has been fun exploring standing waves and Ruben’s tubes to figure out the lyrics to the song. And it’s good to know no matter how many times I listen to it I still get goose bumps.